The Great Rotation: The Case for Intelligent Investing 3D

It's time to invest in the world we see when our screens are off.

For the past two decades, the investment landscape has been defined by a powerful trend: the ascendancy of “Intelligent Investing 2D.” The two-dimensional realm of screens, software, and digital engagement has captured the lion’s share of global capital by offering near-infinite scalability and near-zero marginal costs.

The emergence of Generative AI fundamentally fractures the economic logic of this digital hegemony. By collapsing the cost of digital creation of code, content, and even intellectual property, AI is commoditizing the very assets the market is valuing most highly.

We stand at the cusp of a major capital regime change. As the digital world begins to drown in a deflationary supply shock of its own making, the three-dimensional world of atoms, energy, metals, and infrastructure is entering an era of scarcity. The “playbook of the last thirty years is broken,” according to Will Thomson of Massif Capital.

2026 may be retrospectively identified as the pivot point where antifragility shifted from the owner of the software company to the owner of the copper mine. What follows is an examination of this impending bifurcation and the case for a strategic reallocation into real assets.

A Tale of Two Worlds

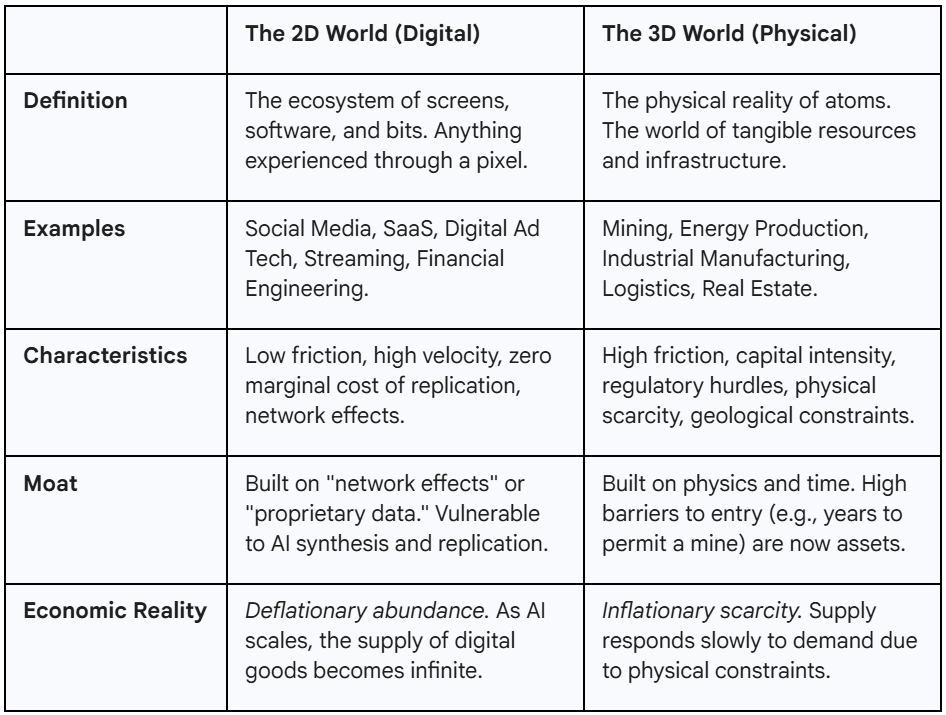

AI is a tech marvel reshaping human productivity. But while investors bid up the creators of this digital intelligence, a more profound shift is underway. The global economy is approaching a stark divergence between two distinct ecosystems: the “2D World” of screens, software, and bits, and the “3D World” of energy, infrastructure, and atoms.

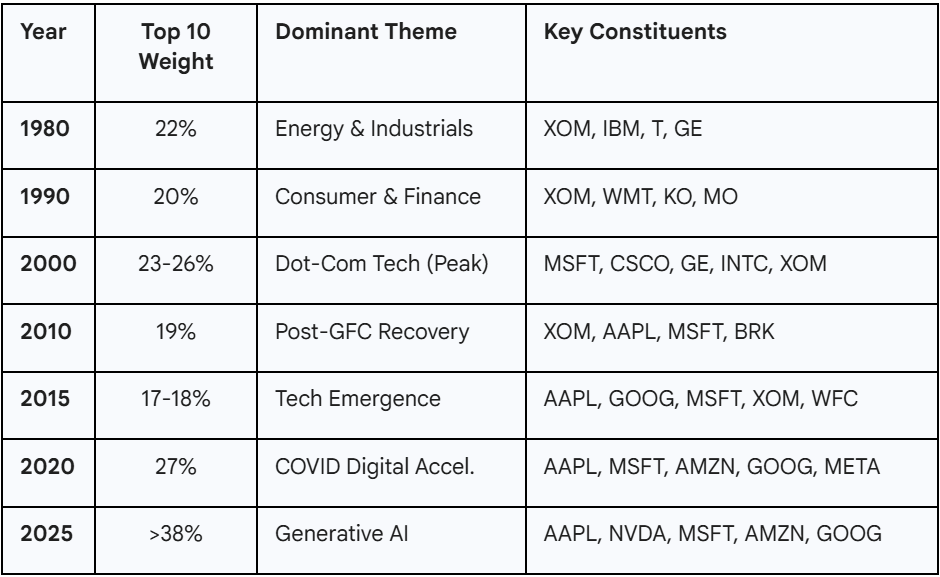

For the past fifteen years, the 2D World has been the only game in town. It offered zero marginal costs and infinite scale. A piece of software code can be replicated a million times without spending a penny on steel, fuel, or shipping. The economics of “infinite margin” rightfully seduced the financial world, ultimately leading to unprecedented concentration in the S&P 500.

The rise of Generative AI is a double-edged sword for this 2D dominance. By democratizing code and content creation, AI is unleashing a near-infinite supply shock upon the digital economy. It is commoditizing the very things that the market has been trained to value most. When an AI agent can write code better and faster than a human, the value of a “SaaS wrapper” collapses. When an AI can generate text, images, and video instantly, the value of digital media inventory approaches zero.

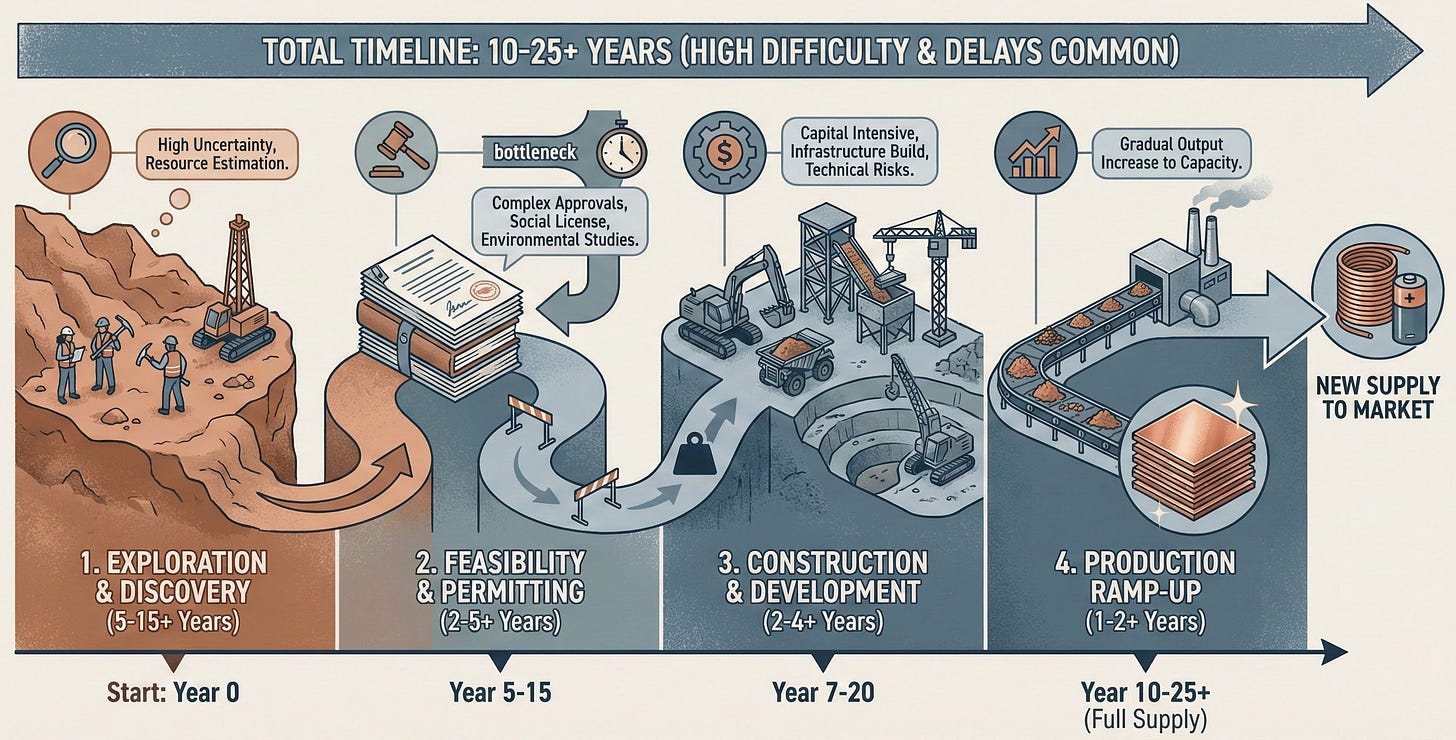

In contrast, the 3D World is facing a supply cliff. As Will Thomson points out, one cannot “prompt” a new copper mine into existence. One cannot “generate” a gigawatt of baseload power with an algorithm. The 3D world is governed by the laws of physics, geology, and thermodynamics, not Moore’s Law. Overlay that with the political forces regulating the 3D word, and it is clear that the addition of supply in the real world remains a slow, painstaking process.

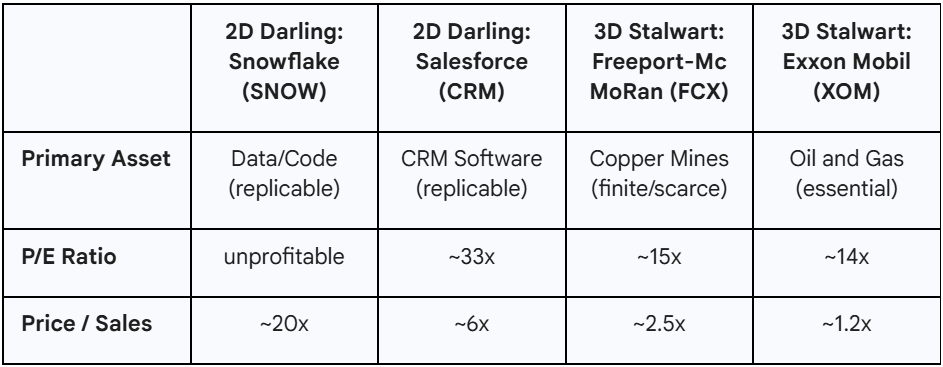

Exhibit 1: Key Differences — 2D versus 3D

The Prevailing Bias

For many investors, the psychological difficulty of this necessary rotation cannot be overstated. The market has been conditioned by more than a decade of “Tech Exceptionalism.” Since the Global Financial Crisis, the prevailing narrative has been that technology is the only sector capable of growth in a low-growth world. This belief has become so entrenched that it is now treated as a law of nature rather than a cyclical phenomenon.

Similarly, the belief in “US Tech Exceptionalism” has driven US outperformance for years. Investors have crowded into the same trade (long US large-cap growth, short commodities and value), creating a “suction pump effect,” as described by Murray Stahl of Horizon Kinetics. This effect pulls capital out of the broader market and concentrates it into a handful of mega-caps, distorting valuations.

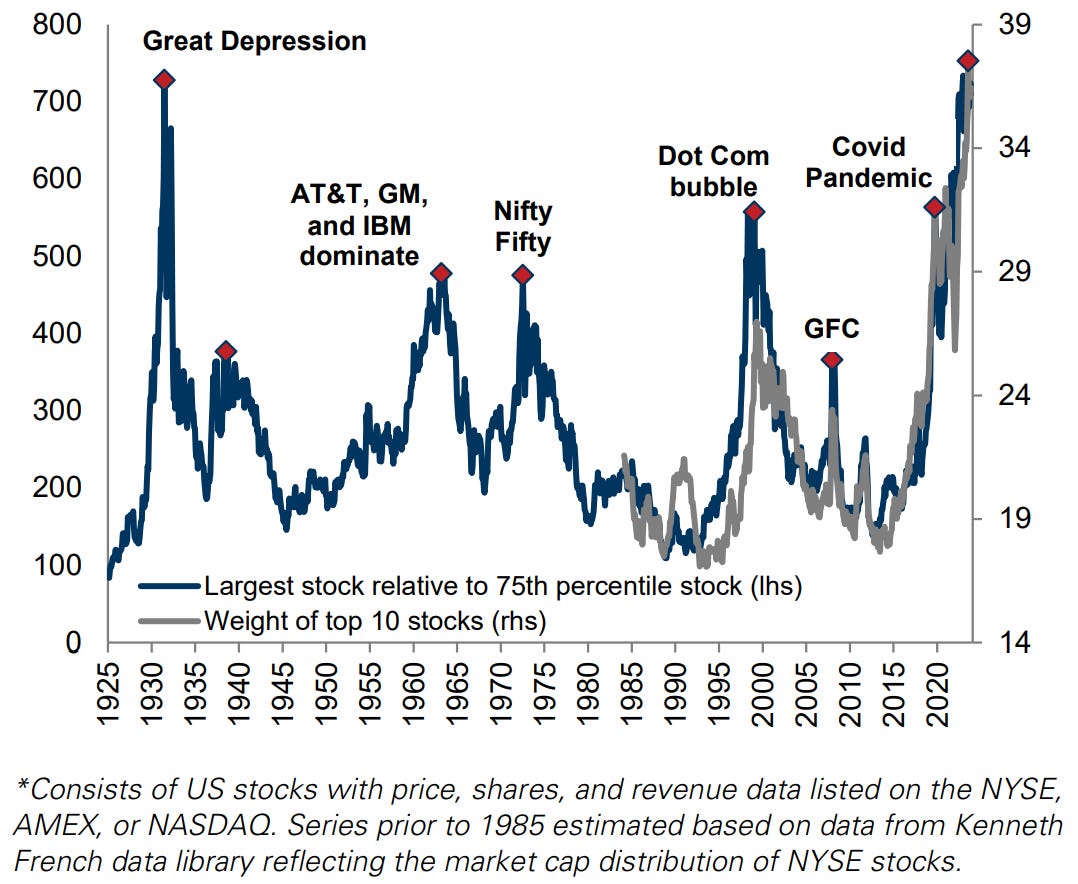

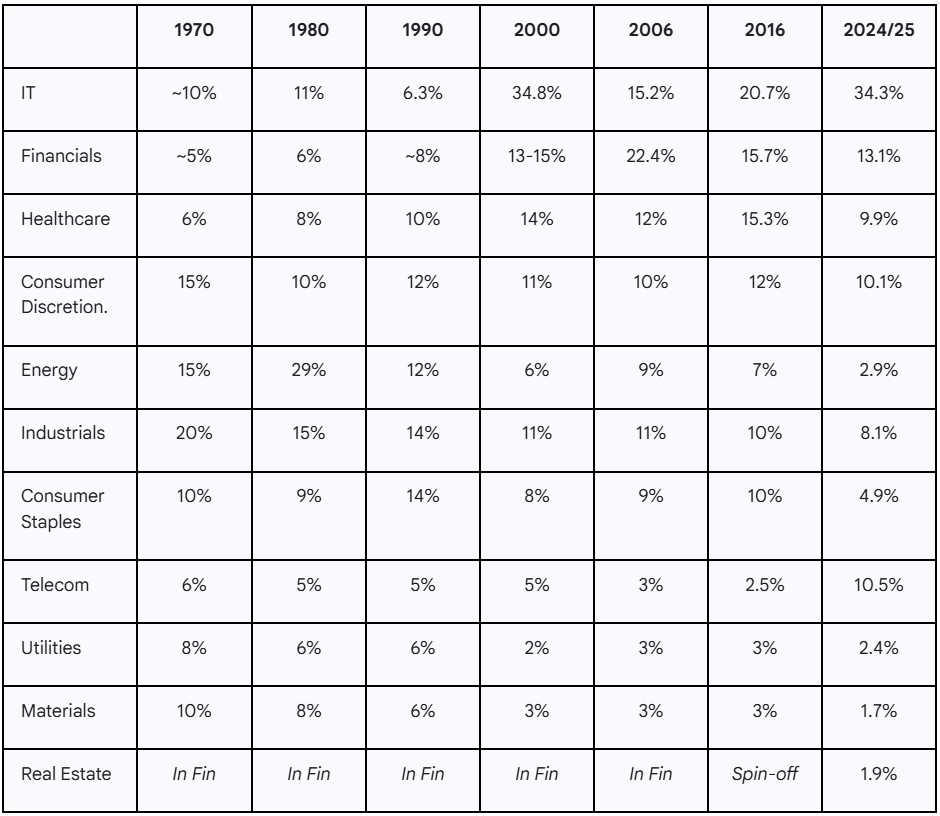

In investing “what worked yesterday” is often the enemy of “what will work tomorrow.” The market is pricing much of the 2D world for perfection, essentially assuming that margins will remain high forever, while pricing much of the 3D world for extinction. This is the classic setup for a capital cycle reversal. The Mag 7 recently comprised nearly 35% of the S&P 500 market cap, a concentration that leaves passive investors exposed to a change in regime.

Exhibit 2: The Evolution of S&P 500 Market Cap Concentration

AI as an Inflationary Force

The central insight here is counter-intuitive. Many investors view AI as a purely deflationary force because it lowers the cost of labor and intelligence. While this is true for the 2D economy, AI is an inflationary force for the 3D economy.

The irony of the AI age is that it is voraciously physical. The cloud is made of steel, and the data center runs on electrons. An AI query consumes significantly more energy than a traditional search query. The build-out of AI infrastructure (data centers, grid upgrades, cooling systems) requires massive amounts of copper, aluminum, and baseload power.

AI acts as a siphon: it drains value from the digital layer (by increasing the supply of digital goods) and injects value into the physical layer (by increasing demand for physical resources). We are standing at the precipice of a Great Rotation where capital is destined to flee the deflationary, oversupplied 2D World and flood into the inflationary, scarce 3D World. Choosing to get ahead of the Great Rotation is not a speculative act. Rather, it is defensive.

Some may argue that AI will be deflationary in the physical world as well because it will make commodity extraction and production more efficient. Such an outcome is possible, even likely, but it seems out of reach for at least a decade or longer. It is certainly much more remote than AI collapsing pricing in the 2D World.

The AI Eraser

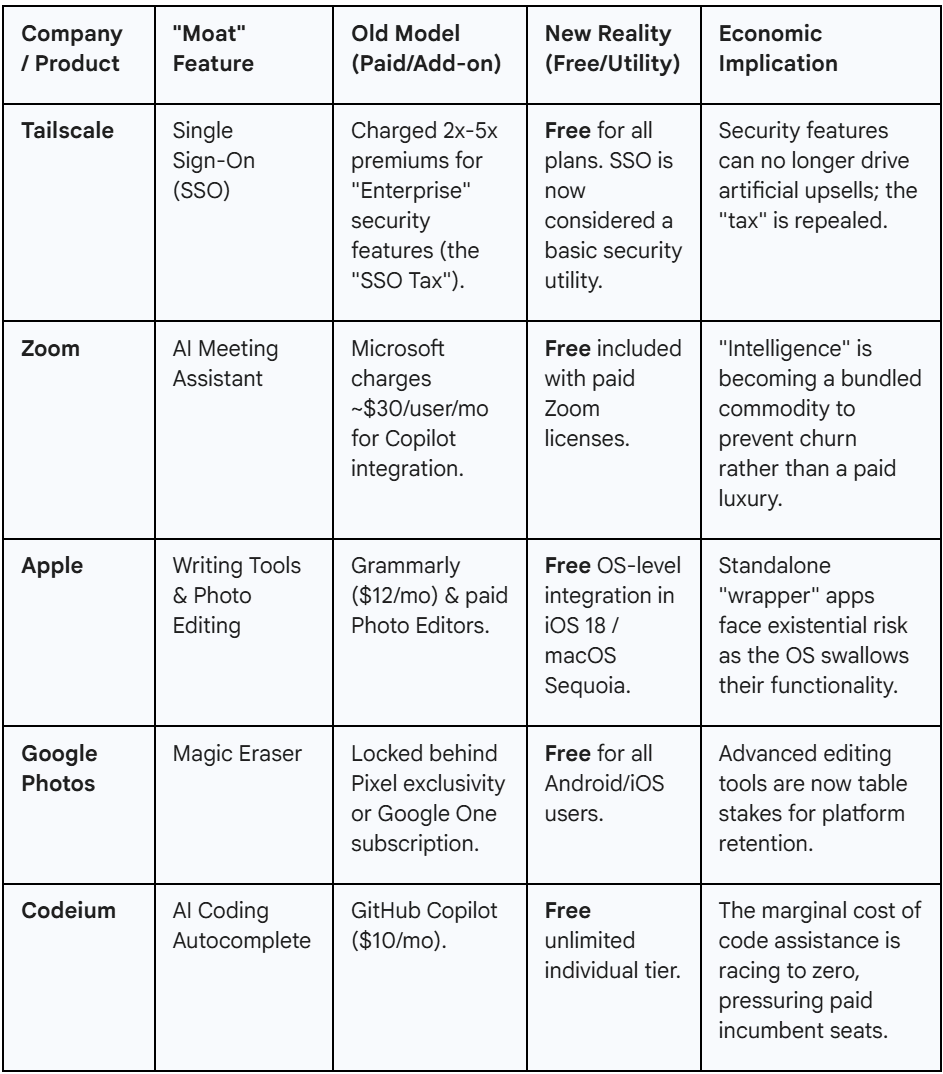

The investment thesis for software has been bolstered by “high switching costs” and “proprietary code.” Generative AI acts as an eraser for these advantages. Consider the SaaS business model. Valuation multiples of 10x, 20x, or even 50x sales have been justified by the idea that once a customer is acquired, they will pay a subscription with 90+% gross margins, essentially forever. This model relies on the difficulty of coding and/or migrating to a competing product.

AI agents are close to being capable of replicating the functionality of many SaaS products, with agent functionality improving rapidly. If an enterprise can use a generic Large Language Model (or a more optimized derivative) to perform the same analytics, customer service, or data processing tasks for which they previously paid a specialized SaaS vendor, the pricing power of that vendor evaporates. We are already seeing signs of a “pricing collapse” in the software sector, where features that were once paid add-ons are now expected to be free utilities. This goes well beyond the typical deflationary forces in the sector.

The implications for a product such as Blinkist, which provides book summaries, may be undeniable, but those same implications also apply — with a modicum of imagination — to a much broader array of software and content.

Exhibit 3: Recent Examples of 2D Pricing Pressure

Exploding Supply and Margin Compression

In the 2D world, supply is quickly becoming near-infinite.

Content: The cost to produce marketing copy is becoming negligible.

Code: The cost to produce an application is trending toward zero.

Analysis: The cost to synthesize complex data is plummeting.

When supply becomes abundant, price collapses. This is the deflationary tsunami facing the 2D world. The moats that investors thought existed are drying up because AI can replicate them quickly and cheaply.

Even in Vertical SaaS, a segment many investors have considered immune, the threat appears acute. The consensus has been that companies providing specialized software for niche industries like construction, legal services, or hospitality are immune to the pressures facing generalist tech. Vertical SaaS products are considered “hard-wired” into customers’ fragmented legacy systems, creating high switching costs. In addition, Vertical SaaS sales teams understand the specific nuances of a customer’s industry, acting not only as vendors but consultants.

Yet, in a world of infinite 2D supply, those are not sustainable moats. AI changes the physics of data integration, as an AI agent does not need a brittle, hard-coded API to talk to a legacy database; it can interpret the data schema, read the documentation, and write the integration code. Or, more radically, it can simply ingest the unstructured data from the legacy system and restructure it on the fly. When an AI agent can serve as a fluid, instant bridge between any two systems, the value of the Vertical SaaS incumbent’s proprietary “plumbing” falls toward zero.

Similarly, the solution-based sales moat is crumbling. In the AI era, the customer no longer needs a vendor to dictate best practices. A construction manager or a law firm partner can prompt an AI model to “design a workflow for managing Tier-2 supplier contracts” or “optimize the patient intake schedule.” The information asymmetry that allowed Vertical SaaS sales teams to charge a premium for “solutions” is disappearing. Even if we are rightfully skeptical of claims that today’s AI can do all of the foregoing, time is decidedly not on the skeptics’ side. What multiple should we put on a business whose moat might be gone in five to ten years?

A Combustible Cocktail: Tech Exceptionalism X Passive Investing

Murray Stahl has poignantly identified the structural risks from an investor’s perspective. The IT sector, inclusive of Amazon, Meta, and Alphabet, recently comprised ~46% of the S&P 500 market value (see page 3 of Horizon’s Q3 letter). If AI makes “intelligence” a commodity, IT sector margins will inevitably compress. The 2D world is entering a war of attrition where the only winner is the consumer, not the shareholder (and even the point about the consumer is debatable due to the quality-of-life implications of the addictive nature of screens and the non-negligible existential threat of AI).

Exhibit 4. Market Cap of Largest US Stock Relative to 75th-Percentile Stock (x) (left axis); Weight of Top 10 Stocks in S&P 500 (%) (right axis)

The mechanism of tech overvaluation is the rise of passive investing. Fund manager Daniel Gladiš discussed eloquently the perils of indexing in a recent interview.

A timely example of the value-destructing reality of passive investing is the impending addition of Carvana to the S&P 500 Index. The shares jumped nearly 10% on the announcement, having already risen 113% year-to-date and witnessed relentless insider selling throughout 2025, in part at materially lower prices. Surely, this is an opportune moment for pension funds and endowments to create value for their beneficiaries by acquiring Carvana shares.

The passive investing trend has created a “suction pump,” according to Murray Stahl, where capital flows blindly into the largest-capitalized companies regardless of valuation. This creates a feedback loop: the higher the stock price goes, the more weight it gets in the index, and the more capital it attracts. This has divorced the price of 2D assets from their fundamental economic reality.

This mechanism also works in reverse. If the underlying fundamentals of the 2D world deteriorate, the “suction pump” will reverse, leading to a liquidity crisis in the very stocks everyone owns. There is “nowhere to hide” in the index when the dominant sector corrects.

Exhibit 5. S&P 500 Sector Weightings

Let’s not forget that the 2D world is constrained by a hard physical limit: human attention. There are only 24 hours in a day. As AI explodes the volume of digital content, the value of an incremental unit of digital engagement approaches zero. We are drowning in “digital noise.” This degrades the value of digital advertising, the lifeblood of the 2D economy. Sure, the creators and companies able to capture scant attention will win, but how do we find them? Nearly every highly valued public company seems like a future winner, but the underlying math does not favor such a conclusion.

Scarcity Premium: The Renaissance of 3D

While the 2D world drowns in abundance, 3D remains constrained. The physical domain is defined by friction, and that friction is now the source of value.

The 3D world has been in a bear market for most of the last decade. Capital has fled the sector since the commodity peak in 2011, resulting in massive underinvestment in productive capacity. As Will Thomson notes, we are moving from an era of globalization and abundant resources to an era of “unwinding” interdependency and resource nationalism.

The “Intelligent Investing 3D” thesis is bolstered by capital cycle theory, popularized by Marathon Asset Management. The theory states that high returns attract capital, which leads to oversupply and lower returns. Conversely, low returns repel capital, leading to undersupply and higher returns.

The 2D world appears to be at the peak of the capital cycle, while the 3D world is at the trough. For a decade, mining and energy companies have been punished by ESG mandates and shareholder demands for dividends over growth. They stopped exploring and stopped building. Bank credit dried up, as pointed out by Mohnish Pabrai in reference to the coal sector.

Meanwhile, oil wells and copper mines deplete every year. If you do not reinvest, supply shrinks. As a result, we have a coiled spring of potential returns. The world has consumed the surplus capacity of the 3D world, and now, just as demand is inflecting upward (driven by AI), supply is hitting a wall.

Goehring & Rozencwajg make a nuanced distinction in the commodity landscape between cyclical weakness and structural strength. In their recent commentary, they split the commodity complex into two camps: (A) Uranium, gold, and platinum group metals have remained “stubbornly immune” to economic malaise because their supply deficits are so acute that they override cyclical demand fears; and (B) oil and base metals, which have reacted to fears of recession and tariff-induced trade wars.

This split may present an entry opportunity. The “Camp B” assets are being priced for a recession or worse, while the gloominess may be overshadowed by secular demand from the AI buildout. The “Next Inflationary Surge,” according to G&R, will lift all boats in the 3D sector, but the entry point today is most attractive in the unloved cyclicals.

It is also instructive to look at the “Return on Invested Energy.” As geology degrades, it takes more energy to get resources out of the ground. We are moving from the “easy oil” and “high-grade copper” era to a period where resource extraction is more energy-intensive and capital-intensive. This raises the floor price for all commodities. The 3D world is not just scarce; it is becoming structurally more expensive to access, granting immense pricing power to the incumbents who own the high-quality assets. Exploration and production, aided by AI, may be an offset in the future, but such a future appears quite remote at this point.

The Great Convergence: Why 2D Needs 3D

The most critical misunderstanding in the market today is the belief that the 2D economy is independent of the 3D economy. In reality, the 2D world is parasitic on the 3D world. It seeks to consume rapaciously the energy and materials of the physical world. As we move from “traditional computing” to “AI computing,” the physical toll of the digital world is skyrocketing.

Energy intensity: Training a single large AI model consumes gigawatt-hours of electricity.

Inference costs: Every time a user asks a frontier model a question, a server farm spins up, consuming electrons and generating heat.

Data centers: These are not virtual entities. They are massive industrial warehouses packed with silicon, copper, and steel, requiring water for cooling and backup diesel generators for reliability.

The bottleneck for the AI revolution is not Nvidia chips; it is the copper wire and the power plant. According to data synthesized from Massif Capital and Goldman Sachs, an AI hyperscale data center is estimated to be four times more copper-intensive than a traditional data center. A facility may require between 3,000 to 5,000 tonnes of copper for power distribution, grounding, and connection.

Goldman Sachs projects that AI-driven demand is pushing the copper market into an imminent structural deficit. Fast-forward ten years and the global supply gap could swell to six million tonnes, a shortfall that is mathematically impossible to fill with currently commissioned mine projects.

Exhibit 6: The Long Journey of Bringing New Copper Supply to Market

We are seeing a shift from demand constraints (where we worried about the economy slowing down) to supply constraints (where the economy literally cannot grow because we lack the physical inputs). In this environment, pricing power shifts to the provider of the bottleneck. If Microsoft needs copper to keep its $100+ billion AI investment running, it will pay a higher price. Demand is mostly inelastic.

The same logic applies to energy. The AI buildout is colliding with a grid that is already strained by the “green transition” and the electrification of vehicles. We are asking the grid to do two impossible things at once: retire dispatchable fossil fuel power (coal/gas) and add massive new load from AI data centers.

This leads to the “Greenflation” and “Tech-flation” thesis championed by Will Thomson. The demand for reliable, baseload power (nuclear, natural gas, hydro) is set to explode. The 2D world’s need for 99.999% uptime cannot be met by intermittent wind and solar alone. This will drive a renaissance in “old economy” energy sources that can provide the stability AI requires.

As noted by Massif Capital, we are already seeing the “bright spot” in European industrials related to power grids and energy infrastructure. This is the leading edge of the Great Convergence: the digital world paying a premium to the physical world.

Historic Valuation Disconnect

The divergence in valuation between the 2D and 3D worlds offers the most asymmetric opportunity set seen since the dot-com bubble burst.

Investors are paying ~20x sales for Snowflake, a business that consumes capital rather than returning it, and whose core value proposition is under threat from commoditized AI analytics. Even mature giants like Salesforce trade at multiples that imply their moats are sustainable. Conversely, the market is pricing Freeport-McMoRan as if copper is a stagnant industry. Freeport owns the Grasberg mine, a geological anomaly that cannot be replaced.

Exhibit 7: A Few Examples of the Disconnect

Bob Robotti offers a crucial correction to the standard “value rotation” narrative. He argues that we are poised to writness not merely the “Revenge of the Old Economy,” which implies a temporary, cyclical bounce. Rather, it is the “Metamorphosis of the Old Economy”. Bob shared his views on the resurgence of North American cyclicals and commodity-based businesses at Latticework 2025.

Industrial companies have spent the last decade consolidating, cutting costs, and cleaning up their balance sheets. They are no longer the bloated giants of 2011; they are lean, cash-generating machines. They have transitioned from being “disadvantaged” by globalization (which favored cheap labor and outsourcing) to being “advantaged” by near-shoring (which favors domestic capacity and reliability). They are trading near liquidation values despite being the essential engines of the future economy.

Resilience and Antifragility

In a deglobalizing world, the physical location of assets matters. We are entering an era of “friend-shoring” and resource nationalism. Access to physical resources is no longer just a commodity trade; it is a matter of national security.

Will Thomson notes that the next decade will be dominated by the “use of trade as a tool of government statecraft”. Owning a copper mine in Arizona is fundamentally different from owning one in a hostile jurisdiction. 3D assets within secure borders are “antifragile”; they gain value during geopolitical chaos because they represent security of supply.

By comparison, 2D businesses are vulnerable to platform shifts (e.g., Apple changing privacy settings), algorithm changes (Google Search updates), and cyber warfare. A software company can lose much of its value overnight if a competitor releases a better AI agent. A copper mine cannot be “disrupted” in the same way. The rock is still in the ground, and the world still needs it.

Then there’s inflation. Murray Stahl provides the critical nuance here: even if official CPI looks tame, “localized inflation“ in scarce assets is rampant. Stahl uses the example of the Sabine Royalty Trust (SBR), an oil royalty company (a hard asset proxy) that simply collects a percentage of the top line. As oil prices rise, the royalty check rises without a commensurate increase in costs.

3D assets are natural hedges against the debasement of fiat currency. If the dollar loses value, the copper mine (priced in dollars) gains nominal value. 2D assets, which rely on long-duration cash flows discounted back to the present, are in a bind if long-term interest rates rise due to inflation while pricing power vanishes due to AI.

The 2026 Pivot

The central thesis of this essay has been playing out already to some extent. However, we are still in the very early innings.

It would not surprise me if 2026 turns out to be the first year of “The Great Rotation.” The initial hype of AI appears like to settle. The market may recognize that the 2D world is fighting a deflationary war of attrition, while the 3D world is enjoying pricing power born of structural scarcity. The narrative may shift from “software eats the world” to “software needs the world.”

For investors and allocators, waiting to pivot is the more speculative choice. Taking advantage of the still-wide valuation disparity to move capital from 2D to 3D assets at a high “conversion rate” strikes me as not only the defensive but also the forward-looking choice.

Featured Events

Ideaweek 2026 (FULLY BOOKED), St. Moritz (Jan. 26-29, 2026)

Best Ideas Omaha 2026, Omaha, Nebraska (May 1, 2026)

The Zurich Project 2026, Zurich, Switzerland (Jun. 2-4, 2026)

Latticework 2026, Chicago, Illinois (Nov. 10-11, 2026)

The content of this website is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy any security. The content is distributed for informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice or a recommendation to sell or buy any security or other investment, or undertake any investment strategy. There are no warranties, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, completeness, or results obtained from any information set forth on this website. BeyondProxy’s officers, directors, employees, and/or contributing authors may have positions in and may, from time to time, make purchases or sales of the securities or other investments discussed or evaluated herein.